The Little Rocket Man Presents:

An autobiographical story of how I got the East Pad's wires fixed

A comprehensive story containing historical, educational, technical and biographical elements & opinions

by

John Fuhring

An autobiographical story of how I got the East Pad's wires fixed

A comprehensive story containing historical, educational, technical and biographical elements & opinions

by

John Fuhring

Introduction

This

is the first of many storys about my engineering career at SLC-3 (pronounced 'slick three') that I hope to post on my website in the near future.

SLC 3 (Satellite Launch Complex Three) is located South of the Santa Ynez River in the foothills of the westernmost end of the Santa Ynez Mountain chain just before they end at the Pacific Ocean at Point Arguello, California. SLC-3 is only one of several sites on a huge track of land known as "South Vandenberg." The launch complex is built on ancient sand dunes that accumulated there during earlier parts of the Pleistocene when this area was close to sea level (today it is about 450 feet above sea level).

Up until the present day's Atlas 5 program, SLC-3 always had two complete launch facilities so that a space vehicle could be assembled on one pad while the other could be used to launch a completed rocket. In other words, "two pads, no waiting." The two launch facilities were laid out in a generally east-west direction so, unsurprisingly, the eastern most pad was called "The East Pad" and the other was, ironically, called the "West Pad." Clever, no? Both pads were originally designed to assemble, test and launch Atlas vehicles with a short two year (1961-1963) period when little Thor rockets were launched. By the time I got there in 1983, the West Pad assembled, tested and launched the older Atlas 'E/F' models. On the East Pad, we assembled, tested and launched the newer Atlas H model. Later, after we launched the last of the E/F and H models, we modified the East Pad for the newer Atlas II, but more about that later. In both cases the "bird" (the launch vehicle) would gain altitude and "fly" due west out over the ocean and once safely over the ocean, it would begin its flight (roll and pitch) maneuvers that would head it South toward an intended "Polar" orbit. By the way, the line connecting the two pads actually ran from the Northwest to the Southeast and the reason for that I'll mention later.

The two launch facilities were somewhat less than a half mile apart and both were electrically tied to the Launch Control Center or LCC, commonly called "The Blockhouse," by means of hundreds of individual wires that in turn were bundled into several thick cables laying on cable trays in tunnels that ran between the pads and the block house. Each wire carried a single command signal or carried the return status of each command or a wire might carry a single one of dozens and dozens of analogue data channels. This complex was designed and built before the age of digital electronics and so none of the hundreds of wires or any of the cables carried multiplexed digital data.

The LCC (or blockhouse) was a armored and reinforced concrete bunker mostly buried in the ground and able to sustain a nearby blast should a vehicle malfunction and blow up at launch or while under critical testing with propellants aboard. Engineers in the blockhouse, sitting at their control panels, sent commands to load propellants, other commands to test the vehicle's many systems and, if all of those systems looked good and checked out OK, the Launch Control Officer would send an electrical command that would start a complex launch sequence (the Commit Sequence) that would start the engines and launch the vehicle. Within seconds of what was called the "commit start" signal, dozens of things would happen in the vehicle and on the pad, with the final result being the main engines would light off and quickly ramp up to full thrust. At full thrust, the engines would have the power to lift the vehicle and its payload off the pad and into the sky on its way to orbit. That's the way it was supposed to work and I am proud to say that every single vehicle my crew and I worked on during my entire career, it happened just that way. We never lost a mission.

I mentioned earlier that the two pads were angled so that a line connecting them would run to the Northwest, Southeast. This was done so that a launch off the East Pad would not have the rocket fly directly over the West Pad or the blockhouse. You might be interested to know that a year or so before I was hired on at SLC-3, an East Pad launched Atlas E/F had a serious malfunction in one of its booster engines right after liftoff. The rocket got up a hundred feet or so and was headed west, but as it was flying just south of the blockhouse, it did a nearly complete summersault in the air and hit the ground with a tremendous explosion and huge ball of fire. Because the blockhouse was right in line with the explosion, observers a couple of miles away thought that the Atlas had landed on the roof of the blockhouse. Fortunately it didn't, but if it had, the people inside very well might have been cooked despite all the concrete and armor. Or maybe not, who knows? However, one young lady observing the launch from a safe distance, became distraught because it was assumed everybody in the blockhouse, including her fiancÚ had been killed. These large space vehicles, especially right after liftoff, have aboard them several tons of kerosene and liquid oxygen and when they blow up, it is the biggest and brightest fireworks you will ever see. Yes, there was a reason the bird's flight was angled away from the blockhouse and the West Pad.

I was working for McDonnel Douglas (Delta Program) at the time, but because it was going to be a beautifully spectacular nighttime launch, I went out to the Base to watch. By the way, because the Atlas burns kerosene, the flame is as bright as the sun and very beautiful as it ascends into the sky (especially at night). The launch kept getting postponed at the last minute and so, after a couple of aborted launches, I stopped going out and so I missed the fireworks. I was sitting at home (probably writing a computer program) when I heard a "boom" that seemed to come from the South a long way off. I looked at my clock and saw that the boom happened at exactly the time the rocket had been scheduled to lift off. I went outside my house (about 23 miles North from SLC-3), but did not see the rocket in flight as expected. That boom and no rocket to be seen gave me a sinking feeling that something terrible had happened. Sure enough, when I went to work the next morning, everybody was talking about the big explosion and the young lady mentioned above (who worked in my office) was there and very happy that her fiancÚ was safe.

Through extensive fault analysis, the problem was traced to a liquid sealing compound that plugged up cooling channels in a ball shaped thing called "the booster turbopump gas generator" (otherwise known as "the GG"). This lack of cooling caused white-hot gases in the GG to burn through and escape. This jet of super hot gas escaping from the GG then burned through a liquid oxygen (LOX) line (the so-called "bootstrap" line) that fed the GG. With the LOX to the GG cut off this way, the turbopumps stopped pumping and the associated booster engine (the B2 engine on one side) stopped working throwing the rocket completely off balance and causing it to somersault. This failure and its analysis resulted in improved shop practices that made the Atlas E/F rockets even more reliable.

In the years since that incident, I have watched detailed films of the entire spectacle from lift off, to the rocket turning an almost full somersault, to the rear of the rocket hitting the ground and exploding. Seeing the two remaining engines and the two little veneer engines hard over and trying desperately to make up for the missing thrust of the third engine, watching the Atlas in its death throes is an emotional thing for me. As strange as this may seem, these films are beautiful, but in a truly terrible sort of way. As an engineer who was very closely involved with the electronics that controlled the movement of the main engines, I could really appreciate what the guidance system was trying so desperately to do as if it was almost human.

Atlas 76E doing a somersault

The payload was an early GPS

The official history states that the rocket was destroyed by a destruct signal from the Range Safety Officer,

but it is obvious from watching the films that the destruct signal was not sent or if it was sent, it was after the vehicle had

already exploded. Things happened just too quickly and the vehicle was not high enough for a destruct signal to be issued.

You may also be interested to know that the very first GPS experiments rode up to orbit on Atlas E/F rockets launched off the East Pad. The early GPS test satellites tried different kinds of atomic clocks until the model presently in use was finally developed and perfected. Even with all the bugs and problems with atomic clocks, these launches proved that the GPS concept was sound and it was worth developing. Consider how ubiquitous and how supremely important GPS is in our lives today. In many ways today's GPS is thanks to the experiments launched off SLC-3 East Pad. By the way, the spectacular launch failure mentioned above carried a GPS test satellite.

I had originally started to write a long-winded story about how the Atlas family of space boosters came into being because of "our German Scientists" including the (in)famous Werner von Braun, but that really is another story and this is not the place, nor am I the person to retell it, so I'll try to get right into my story.

A Brief Description of SLC 3 East and West Pads

Each of two

launch mounts (SLC-3 East and SLC-3 West) had an associated Mobile

Service Tower (called the MST or simply "the tower"). These

towers were tall skyscrapers with a strong skeleton or frame of steel

and they were mounted huge steel wheels that ran on four parallel

tracks that ran away from the launch mount on a long level surface

called the launch deck. Each of the wheels had a hydraulic motor

that was operated by pressure from a powerful pump that was located

below in the M & E rooms below the launch deck.

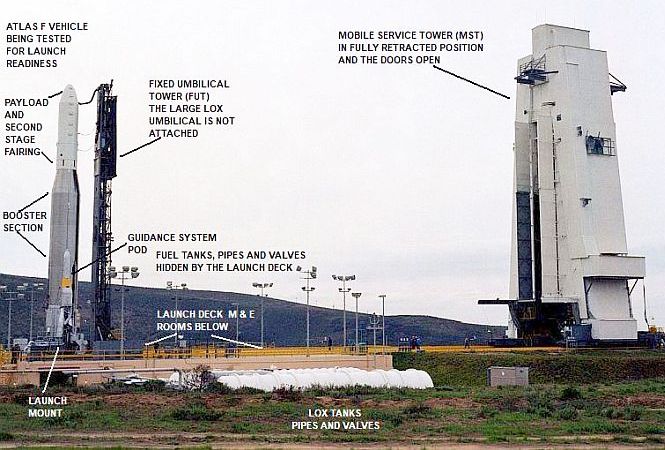

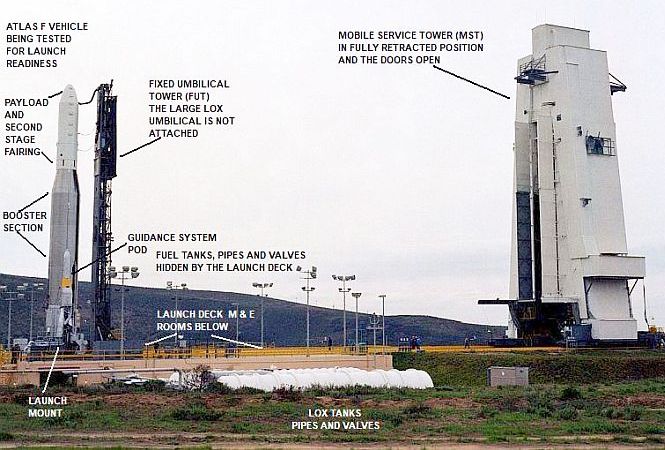

| SLC-3E before conversion to launch the Atlas H Shown with an Atlas E/F "Rocket in the Socket" The apparent tilt of the rocket is due to distortion in the camera's lens.

The MST would be rolled back for Simulated Flight

(Simflight) where we tested every aspect of the booster engines and

guidance system

and how they interacted with each other. In addition, the

Destruct System would be tested with the MST rolled out. The

Destruct System's purpose was to explode the vehicle if the Range

Safety Officer saw that it was off course and if so, he would send out

a coded Destruct Signal by radio. The Simflight needed to have the engines free to move in response to guidance signals, but no dangerous propellants were aboard and all vehicle ordnance was disabled. The MST would also be rolled back for a "Wet Dress Rehearsal" where propellants would be loaded, everything would be connected including all the many explosive devices aboard the vehicle and a simulated countdown would proceed almost to T-0, but stopped just before the Engine Start signal would be sent. Yes, the Wet Dress Rehearsal was a hazardous operation, the most hazardous operation next to the actual launch. The MST would always be rolled back if there was any kind of hazardous operations going on involving the propellants, or if the vehicle was at flight pressureso that, if the worst should happen, the valuable MST wouldn't be destroyed too. |

This wheeled arrangement allowed the towers to be moved away from the launch mount for vehicle erection, for hazardous tests and actual launch. Normally the MST would be located over the launch mount so that the vehicle could be assembled after it had been erected. The towers had a series of huge vertical doors that opened up and then closed again to completely enclose a vehicle from just above the three main engines all the way to the payload on the very top of the "stack."

Within the MST were several movable and folding floors (we called platforms) that were designed to surround the vehicle at each level. By having the MSTs able to totally enclose the vehicle and with multiple floors on all levels, all parts of the vehicle could be assembled and tested and the vehicle made ready for launch, regardless of the outside weather or the time of day. To enable workers and their equipment to access each level (floor) there was an elevator and a staircase.

Each of the launch sites had their own propellants storage and transfer facility consisting of tanks and equipment to store and transfer liquid oxygen (LOX) and a refined Kerosene called RP1 (or Rocket Propellant One). In addition to the storage tanks, there were a maze of pipes and valves and vents so that propellants could be transferred from tanker trucks to ground tanks, others to fill the vehicle (for testing and for launch) and to drain the propellants out of a vehicle if required. Propellant transfer, especially the transfer of liquid oxygen (LOX), was hazardous and always done by remote control from the block house. It was especially hazardous if LOX and RP1 were spilled onto the launch deck because, if they mixed together they would form a highly explosive gel that was extremely shock sensitive so that if anybody stepped on a blob of it, a dangerous explosion would occur and their foot would be blown off or much worse.

Below the launch mount and the service tower deck was a series of rooms built into the thick concrete bunker that the launch mount was built into. Housed in those rooms (the M & E rooms) were all the electric, electronic logic control, powerful hydraulic pumps and a myriad of machines and other equipment necessary to service and ultimately load and launch a Space Vehicle.

Propellant loading was performed remotely by the Engineers in the LCC who would send commands and receive status indications by means of a set of electrical cables that terminated at cabinets that contained racks and racks of relay logic. Electrical signals from those cabinets controlled the ground and vehicle propellant valves. The relay logic that assisted in the control of the Atlas propellant loading and launch was a reflection of the Atlas' heritage as a hydrogen bomb weapons delivery system.

This rather complex relay logic (affectionately called "the pinball machine") was originally designed so that those less than brilliant young Air Force officers could turn their diabolical 'Keys,' and send the rocket and its hydrogen bomb on its way to wipe out millions of lives in Russia without any of those "not exactly rocket scientists" having to know diddly about rockets, propellants or the delicate internal workings of the Atlas booster. Or at least that's how it was supposed to work, but things, even things designed to be "fool proof," seldom work the way they were expected to work. With something as finely tuned as an Atlas, the unexpected was a common occurrence and therefore it took well trained engineers to closely monitor what was happening and understand it. It took well trained engineers to know what corrective action needed to take place so as not to damage or ruin the vehicle during these hazardous operations. Or worse, an explosion on the pad.

A View Into My Sense of Personal Morality:

A Rant You Can Skip if You Want

A Rant You Can Skip if You Want

Forgive my diversion, but at this point I am compelled to tell you, gentile reader, that I have always considered weapons designed to inflict massive and indiscriminate death on innocent men, women and children to be the ultimate in immorality. These "targets" were unlucky enough to be born in the "wrong" country, but using machines of death dealing technology to murder these human beings in their millions has always been my idea of the most extreme evil. I have never wanted to work on weapons systems of that sort and I avoided even being asked by not applying or in any way wanting a Top Secret Clearance. I like to think that all the missions I was ever associated with were of payloads that did good for humanity and were used to enhance and protect life. Of course, the Evil Lockheed Martin company demanded that all its engineers have this kind of clearance and be ready to join them in whatever evil they need an engineer for, so I eventually lost my job, which was fine with me because by that time I had had more, much more than enough of that evil company their disgusting "management style" and their dumb toadies in the Air Force.

My Impressions of the Atlas E/F

and a Little History

and a Little History

I have to say, these automated systems for launching the Atlas E/F were brilliantly designed by true "Rocket Scientists" in the early to mid 1950's, The Atlas E/F itself was a beautifully designed rocket, lovingly conceived of by Germany's (and some of our own) most brilliant Rocket Scientists. Yes, the whole package was brilliant, but the hard truth is, as a weapons system, the Atlas E/F was just too delicate and too highly sophisticated for ordinary, ham-fisted yahoos in the AF to launch without blowing them up, even with all the automatic controls to try to do the thinking for them. The Atlas family of rockets soon gained a terrible reputation for blowing up and finally the Atlas E/F was "retired" from the weapons inventory of the Air Force and replaced with the much simpler and and easy to launch Titan Booster.

This nearly spelled the doom of the Atlas E/F rocket and indeed many of these brilliantly designed and beautifully made (and incredibly expensive) machines were turned into scrap because there was just no room for these useless White Elephants. When all seem lost, somebody had a brilliant idea: what if we take the old Atlas E/F's and give them to Rocket Engineers who have the education, intelligence and skill to handle the Atlas as it should be handled? What a great idea! Under this new paradigm, whereby this high performance and highly sophisticated rocket was now handled by those who knew what they were doing, the Atlas' quickly achieved brilliant success and a well deserved reputation for great reliability.

So, suddenly, there was an inventory of wonderful launch vehicles that were essentially "free" because they had already been paid for and were now simply "(Cold War) war surplus." But Wait!! Not so fast, first these surplus rockets had to be completely rebuilt. They had to be carefully converted from unreliable "War Birds" into ultra reliable --- and very cost effective --- satellite launch vehicles.

As the old military vehicles would come out of storage (not always in the best condition), they would be given to a crew of well trained and skilled technicians at our Booster Assembly Building (the BAB) on the main side of Vandenberg (North Vandenberg). At the BAB, this elite crew would take off the engines and disassemble all the components right down to the last nut and bolt and wire. Each little part would be cleaned inside and out, new gaskets and sealants would be applied and a brand new wire harness would be built and installed. All the lessons learned in the manned Atlas Space Program would be applied to these vehicles too. When every little part was ready, everything would be reassembled into a rocket that was far better than when it was new. For the low price of just a couple of million dollars, the Air Force Space Program would have at its disposal, a powerful and superbly reliable rocket ready to launch any payload into "Polar" orbit.

Meanwhile Back at the Rocket Ranch

A little Side Trip Back to the Dawn of the Computer Age

A little Side Trip Back to the Dawn of the Computer Age

In the meantime, after use of the Atlas as a weapons system had been abandoned, development work on the later model Atlas' continued. At the time I came to work out at SLC-3, the East Pad had already been converted to support the later Atlas H model and there had already been a couple of launches. To support testing of the Atlas H and its complex ground support systems, an advanced (for its time) microcomputer driven system was designed and built. This test system was based on the (then) famous Z-80 microprocessor and it used the excellent and reliable and popular (for its day) STD Bus as its backbone. The engineer who put this all together, Jim Dodd, was also an expert in the Z-80's Assembly Language. This checkout system, now called PECOS, needed a computer program to tell it how to do its job, so Jim wrote an elaborate and hugely complex program, all in Assembly Language for PECOS. For Jim to have the tools to write and then go through the extensive debugging process, he got company headquarters to give him a professional Advanced Development System that had been made especially for the Z-80. In addition, he was able to get all the other supporting equipment for creating and "burning" the actual (ones and zeros) machine code into PROMS (Programmable Read Only Memory).

Jim got General Dynamics Management to give him all this equipment and then allowed him to design, build and program the PECOS system, just as they later gave me permission to design and build the much more complex ACME system. Such a thing could never, ever happen under Lockheed Martin, but General Dynamics was a whole lot (a whole lot) less rigidly "Top Down" than was Lockheed-Martin and they (GD) gave their engineers a lot of authority and freedom at the local level. When L-M took over from GD, they took away all local design, all local authority and creativity and ordered that everything come out of headquarters in Denver. Engineers were belittled and made into robotic extensions of Denver. As far as I was concerned, this reflected the fact that LM is extremely top-heavy with ex-military brass in positions of management. Lord, I hated working for Lockheed Martin.

It so happened that I had also worked with a Z-80 based control system when I worked for the General Electric Nuclear Power Division and and it too used a STD Bus, so I was already experienced in this "new and exciting" (for the time) technology. To top it off, I had been writing Assembly language programs myself for my Radio Shack TRS-80, an early "8-bit" PC. Oh how I loved those Assembly programs, you could "burn" a program that was perhaps only 1,000 -- 2,000 bytes (not megabytes) into a memory chip and then without any operating system at all, and just a few "chips," your circuit board could do the most amazing things, talking to other circuit boards, writing out messages to displays and printers, taking in information and making decisions on what steps to take next.

These were really heady times for us nerds who loved seeing this magic unfold with things and programs we created ourselves. This was the stuff of wizards and gurus and only Jim and I had the least understanding of Boolean Algebra, the Binary, Octal and Hexadecimal number systems, Bits, Bytes, 16 bit Words, 64K Addresses, memory maps, Assembly Language Mnemonics and logic program structure, Logic Flowcharts, Branching and logic operators such as AND, OR, Exclusive OR, IF Then, all resulting in program branching and decision making within the program. We had to know and create reserved areas of RAM for data, stacks and special functions.

We had to know all about the actual IC "chips" we were using including the Z-80 microprocessor chip. We had to have a complete working knowledge of the internal architecture of the Z80 microprocessor with all its registers, double registers, memory addressing, its Arithmetic Logic Unit, various Stacks including Interrupts (hardware and software), the Interrupt Stack (among so many, many other things). Of course there were a host of other kinds of chips we had to know all about.

Some of the other kinds of chips included, ROMs and RAMs, PROMs (together with their associated PROM burners and PROM erasers), J-K and D Flipflops and One Shot oscillators, A to D and D to A converters, Four Quadrant Multipliers, Opticouplers, Clocking oscillators and Clock Rates. We had to know the difference between the logic families such as RTL (resistor-transistor logic), DTL (diode transistor logic), TTL (transistor-transistor logic) and CMOS logic. We had to understand discrete logic and the individual transistors, diodes, resistors and capacitors that we needed to include in our design. Finally, we had to understand older Relay Logic SLC-3 was originally designed for. We had to know how we could interface with it or, in some cases, replace it with our more modern electronic logic.

To top off all those skills, we had to know how to use an Emulator and Debugger and how to step through a single program command or specific set of commands and then compare what state the logic was in at each pin of each chip with what it should be according with our software design. Working in conjunction with the Debugger were Logic Analyzers, both multichannel and single probe types together with logic pulser probes to set logic states so we could see if the program was catching them properly. All this to catch those very elusive and incredibly difficult "program bugs" that caused unexpected and unwanted logic states or wrong data. Once the "bugs" were caught, then came the hard part of figuring out how to fix the software.

There were many times where I'd work all morning on a really tough bug there in my lab and I get more and more frustrated. When noon rolled around, I would have to force myself to take my noon walk. I didn't want to go, but I had this routine and I stuck to it no matter what. While on my walk, while my mind was a thousand miles away, suddenly, unexpectidly and seemingly coming out of nowhere, the key to bug would hit me in a kind of mental flash. When I'd return to the lab, there it was and within a few minutes I'd have a fix for the bug I had worked all morning on.

I nearly forgot to mention the STD Bus and how to use it with the myriad of plug-in circuit boards that were available for the STB Bus. For special complex functions that nobody made a board for, I had to design and have our technicians manufacture several custom circuit boards right there in my little labratory the company let me have. Oh yes, it was wizardry and deep, almost occult knowledge and a highly creative art and science that few people really understood as we did, but, as we said in those days, "if you understand a technology, it is already obsolete." There were many other things that I had to know, but this list is long enough.

One day Jim walked into the Site Manager's office and asked to be paid what he was worth, but our management was stuck in the old electromechanical days, had no understanding of the power of digital electronics and had no idea what a talent they had and so they wouldn't meet his salary demands. He quit, right there he resigned. I don't know this for a fact, but I believe Jim thought that they would soon learn what a huge mistake they had made and beg him to come back. However, my presence and expertise threw in a monkey wrench and made it unnecessary for the management to relent.

Looking back, me seamlessly jumping in when Jim left made it too easy for those creeps to disrespect real talent and I, myself, added to management getting away with denigrating Jim and, by extension, the rest of us "nerds" who actually know how make things and make things work. It so happened that I was ready to take over Jim's lab and his Advanced Development System and not only understand and maintain all his microprocessor based creations (that nobody else had the least clue about), but to start designing new, even more sophisticated and elaborate microprocessor based pieces of equipment and to write all those magic programs to make them sing.

Forgive me, but I just realized that I have gotten seriously sidetracked and should now get back to the main story, but that's just typical me, I always go into too much detail and background. Anyway, back to the story.

The End of the Atlas H and changes necessary for

The New Atlas II

The New Atlas II

Like all things, even the 'new' Atlas H became obsolete and so after several years of remaining idle with no 'H' launches off of the East Pad, Top Management began to tweak the Air Force and finally got them to approve a conversion of the East Pad so that it could be used to launch the newest Atlas II series of space boosters. The company finally got the Air Force to agree to a conversion of the East Pad, but due to the rigid and highly compartmentalized budgeting rules that the Air Force operated under, the money had to come from an "under the table" source.

By tapping into an obscure budget reserved for maintenance of existing systems we finally got the money for the conversion. Of course, the Company would never have considered putting up its own money, but would only do things (like building a new launch pad) if the Government, through the Air Force would pay for it up front. These so-called "Defense Contractors" like Lockheed Martin have the best of both worlds. With regard to making anything, from a screw to a whole rocket, they first form an arrangement with the U.S. military that is pure Socialism, but at the same time, they are allowed to give their CEO's millions and millions of dollars in salary and millions more in "bonuses" that would never be allowed in a less hybrid (and less corruptible) system.

It was the consensus of just about everybody who knew anything about building a launch complex that it would have been very much quicker and more importantly, very much cheaper if the East Pad would have been completely bulldozered down to the dirt and a complete new complex built and built with all the foundation, construction and electrical layout done to the state of the art. With a new, state of the art pad built and everything in place, (with me in charge of designing electrical test equipment) we would design and build all of our own modern launch control and test equipment right on site. With the latest and greatest electronic equipment, we'd have an ultra-modern, state of the art launch control and comprehensive testing system that would be better than anything in existence, or so I dreamed.

There is one major thing that was done right and that is the construction of a really deluxe new, robust and tall Mobile Service Tower (MST). Of course, the old MST was too small and too corroded by years of exposure to salt spray from the ocean to consider upgrading and reusing. It was also an absurd idea to try to copy the Florida's MST because it was really a rusted piece of junk not worthy of emulation.

BUUUUTTT, we were dealing with the Air Force and we were dealing with a company that is, like the Air Force, completely rigid and completely top-down, so I think you know where this is going. Yes, there was no starting afresh, we were to take the design of an old launch pad there in Florida with its pre-1950's technology still in use and make our Atlas II pad an "exact" copy of it. The project was sold this way as a way of saving money. It was at this time I made up another one of my new "Old Sayings: "the Air Force was going to save money on this pad no matter how much it cost" and it ended up costing plenty. By the way, I just love "old sayings" and just love making up new ones.

All the endless man hours we had to expend to convert the old East Pad for the Atlas II is really beyond the scope of this story, so I won't get into all of it here. There is one important aspect that I will mention and that is how we were to go about the task of remaking the old Atlas H pad into an exact copy of an old, but operational Atlas II Florida pad. We began by using the drawings and design criteria directly from the archives of the Florida pad's Design Department. It was quickly apparent that these design drawings weren't all there, were not up to date and not collated properly, so we had to sort of piece things together ourselves. Little did our management or the Air Force know (or care) that these drawings and specifications hadn't been kept up to date for years and years or, in some cases, had never been recorded in the first place. It was clear to me that the Florida Atlas operations did not have the talented and conscious Design Department that we always had.

On a personal note, I will say that I was amazed and angry and severely disappointed to learn that we were simply going to copy this grossly obsolete and poorly designed Florida technology and we were supposed to do it with poorly documented drawings instead of doing things right from the very start. This is how the company sold the project to the Air Force and, by golly, that's the way were going to do it.

How "Defense" Contractors do Engineering and Make Unconscionable Profit these days

No Wonder We Spend so Much Tax Money on the Military

No Wonder We Spend so Much Tax Money on the Military

It turned out that metamorphosing our old East Pad into a (more or less) exact clone of an operational Atlas II Pad in Florida was much more wasteful, slower and error prone than even I had feared. None of the drawings that were supposed to show how all this was to be connected up were in any way up to date or at all accurate. Over the years and decades, changes and additions were made to the Florida pad that were not documented or documented very poorly so that when all the new wiring was installed per those very poor drawings, almost nothing worked but there sure were a lot of burned wires. Almost literally, toilets would flush when you tried to turn on a circuit or start a motor running.

Well, the company had contracted to rebuild the East Pad according to the design of the Florida pad and everybody (but me) simply PRETENDED that the drawings were current and accurate (which they certainly were not) and with their eyes wide shut, they proceeded full speed ahead. Everybody knew that the drawings we had to work with were garbage and that nothing would work right (if at all) and it would be dangerous and irresponsible to try to put an Atlas II vehicle on that pad, but nobody was supposed to say anything. After all, the Company's Top Management never promised the Air Force that we'd hand them a WORKING launch pad, only a launch pad built "exactly" as the Florida's documentation specified. We all knew that it would be impossible to launch an Atlas II vehicle from the East Pad, but the job was "sold" to the Air Force, and the Air Force accepted the "finished" project in a little ceremony there on the launch deck. Because the East Pad had been built exactly as specified by these inaccurate and incomplete drawings, the task was officially accepted as complete by the Air Force.

I treated this whole thing as a lie, a scandal and an obscene joke, but the company got its money, and the higher management got its bonuses for "completing on time and on budget," but now the real task, to make everything actually work, had to somehow begin. Another contract was made with the Air Force to correct all the mistakes and bring all the drawings up to date so that a real Atlas II could be assembled, checked out and launched from SLC-3E. In this way, the company could bleed more money from the stupid Air Force and get away with not doing it right the first time.

There we were, stuck with a useless pad and stuck in the mud

One of the first things that we needed to do was to track down all the undocumented changes that were missing from the Florida drawings. We needed to know where all the new wires went and how to get all the electrical commands and signals to where they should go. To do this very complex investigation in our traditional way was patently impossible. Our method of troubleshooting and discovering errors was designed for a system that is complete and functional, but might have one -- just one -- fault that had to be investigated, completely understood with all other possibilities eliminated, and then, involving several layers of engineering and oversight, finally, finally , finally have in hand an approved method for fixing the malfunction.

To implement this approved method, it would require the presence of the test engineer (who originally wrote the plan) to be there to oversee everything, one or more certified and licensed technicians to actually do the work, the QA inspectors to make sure everything was done according to written instructions, the uniformed military representative (E-6 or higher) to witness the work for the Air Force and the Aerospace Corporation Consulting Engineer, also present to explain to the Air Force staff everything that was being done as it was done in simple language they could understand. Here we were with hundreds of faults in a chaotic mess and our traditional and very careful and slow way of fixing things (as outlined above) was totally (and I mean TOTALLY) inadequate.

Doing it the Approved and Accepted Way would have to be overridden and in its place, intelligent and responsible short-cuts would have to be substituted. With the East Pad in the mess it was in, it would literally take years and years to discover and fix all the bugs using our traditional methods. In short, our usual, highly involved and intricate system of troubleshooting and fixing was way, way too cumbersome for the huge task before us.

The "Secret Agent" and his Merry Men Work in the Dark of Night

What to do, what to do?!? Here we had a very expensive "refurbished" launch pad for the Atlas II rocket that had been rebuilt to be "exactly the same" as an operational Atlas II pad in Florida, but absolutely nothing worked and our own very complex system of troubleshooting, investigating faults and fixing faults had us in an iron straight jacket so that we were paralyzed. When all seemed lost, somebody had a brilliant thought, "let's get John to fix it" (he's not exactly a 'Rocket Scientist' you know), so, as it turned out, it was John to the rescue. I was tapped for this secret mission and I never questioned that I was the ideal person to do it.

In a secret meeting with the top field engineer from the company's headquarters, I was asked if I and a highly select crew of technicians working under me, would use my (infamously creative) skills and my obvious drive to make things work and work right, to secretly track down each of the dozens and dozens of malfunctioning circuits, immediately fix them before investing the next fault and do it without anybody knowing about it (at least officially). Besides this, nobody even wanted to know (even unofficially) just how I was doing it.

Oh Lord!! do I love doing these sort of things, skirting the obstacles and getting the job done even at the risk of being fired or even being investigated by the FBI for working on Air Force launch equipment without going through proper (or indeed ANY) channels. Unlike my engineering colleagues, I had no wife or kids who would be devastated if I got caught and I was one of the few engineers that wasn't hugely in debt and so I could take on such a task, take the risks and enjoy every illegal moment.

My crew and I worked late at night after everybody, including the Air Force had gone home for the night and nobody asked us any questions. I had my own key to the buildings and the guys who worked for me were the best there were and knew how to keep silent. We would work through the night and I would simply direct my guys to connect my special test equipment here and there, run a safe current through a circuit, open cable bundles and use a current probe I had devised to manually track down each and every one of the hundreds of malfunctioning circuits and then fix them. With the help of my crew, I would find out where the errant signals actually went and then connect them where they should have gone in the first place.

It was (in a good way) sneaky, it was a game and a mental challenge and a chance to be creative and it was fun! When we'd discover and correct a fault in the wee hours of the night, I'd record it in a notebook and go on to the next problem. When the day workers would come in in the morning, I'd give my list to those outstanding and highly talented men in our own design department, Jim Morris and Tak Yamatani and they would quietly make changes to the Florida's documentation and make it appear to all eyes as if we had built the pad the correct way to a correct design in the first place.

The Joys of Beating "The System"

Despite having done what had to be done, I want to state up front and candidly that I am, under all other circumstances, a great supporter of the highly refined system of troubleshooting and fixing things that has painstakingly evolved over the years so that today launching billion dollar rockets is safer and more assured than crossing the street. I respect and have always respected the QA (Quality Assurance) and Inspection engineers and technicians and have never, never "gone over their heads" to get something of mine approved. Having said that, there was this one time where playing by our highly complex rules was completely impossible and so we thus come to the climax of this story.

Finally, after some weeks of these overnight operations, my crew had everything correctly connected and all the functions functioning as they should all over the pad, the M & E rooms, the Service Tower and the Block House. Now, when you'd turn on a circuit, toilets wouldn't flush, nor would water dribble from the light sockets any more and every valve and switch and signal and indicator light all over the East Pad was working as it was supposed to. I felt pretty smug about all this, but of course I could not and did not expect any reward or recognition for so egregiously, so incredibly egregiously flaunting our usual and approved system of doing thing. At the time, so many years ago now, I didn't "blow my own horn" but now I am and it is for your amusement and entertainment that I am doing so, gentle reader.

You know, I didn't care that I got no thanks or recognition because, for a Dilbert type of engineer such as I am with an advanced case of "The Knack," the self-satisfaction of successfully cutting through an otherwise huge and impenetrable mass of sticky red tape, of doing what is needed in an inventive and creative way and making the unworkable work is a reward that is beyond all rewards. John Tolkien wrote: "praise from the praiseworthy is beyond all reward" and although I was praised by nobody, I had this personal feeling of supreme accomplishment, as silly and vain as that sounds.

The End

Please look for my story of the VMTS

coming soon.

Having arrived this far,

obviously you have a superior attention span and reading ability that

far exceeds that of the

majority of web users. I highly value the opinion of people such as yourself, so I ask you to briefly tell me:

majority of web users. I highly value the opinion of people such as yourself, so I ask you to briefly tell me:

Did

you enjoy this article

or were you disappointed?

Please

visit my guest book and

tell

me before you leave my website.

If you liked this story or found it interesting, I'm in the process

of writing an even more interesting story of my adventures

while working on a complex Atlas II ground support system,

The VMTS

and will be posting it soon.

If you liked this story or found it interesting, I'm in the process

of writing an even more interesting story of my adventures

while working on a complex Atlas II ground support system,

The VMTS

and will be posting it soon.

If you have any detailed comments, questions, complaints or suggestions, I would be grateful if you would please

E-mail me directly

If you like my stories, tell your friends, if you don't like my stories, tell me.

There a lot of other articles about various subjects you might enjoy, so

Please go to my Home Page